Recently Noah Smith made a tweet seemingly questioning the relationship between demographic processes and feminism, drawn from cross country comparisons from Pew. I understand that this is a tweet, and so that there was not much room to expound a detailed explanation of a theory, but much of the claim seemed to rest on the idea that because the United States had higher levels of childbearing and earlier marriage rates than some countries which are stereotypically stricter in terms of gender norms, this somehow refuted the standard claim that increasing women's agency was associated with lower fertility and later marriage.

There are a number of issues with this supposed refutation, and I'll discuss these in a little detail in the following three sections.

Are cross national comparisons valid?

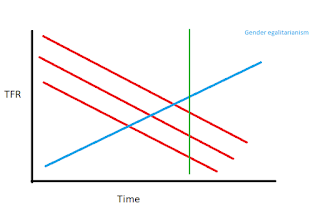

The claim that Noah seems to advance here is that because at one point in time the correlation between demographic outcomes and gender equity is not strongly negative, this refutes the idea that there is an effect here. This seems to fundamentally misunderstand the claim that demographers make: this is that changes over time will tend to decrease fertility rates within the same setting. Considering the stylised diagram, Noah is effectively looking along the green line, and using the variability between countries (red) in TFR to claim there is not correlation between demographic outcomes and egalitarianism.

Now it should be noted that the evidence when looking on a between country basis is somewhat mixed. However, using cross sectional comparisons to draw conclusions about trend over time, without accounting for the starting point (the variation in the country TFR in the example at the green line is solely due to variation at the start, since the slopes are parallel) gives a deeply misleading picture. In reality of course, we are unlikely to see such a neat picture as in the toy example- indeed there is no requirement for societies to transition to low fertility at the same rate with increasing cultural and gender changes under second demographic transitions model. As such, neither the existence of between country demographic variation, nor the fact that there is no homogenous pattern, necessarily refutes the point that gender equality would be associated and perhaps causally with decreases in fertility rates.

What is the model of change?

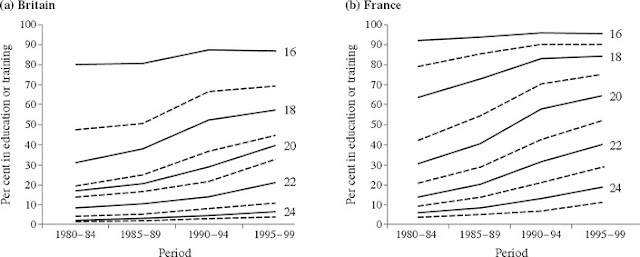

Another problem is that Noah is incredibly unspecific with his terminology, so we don't have a real logic of change model to deal with. One of the major transformations we have seen that would be widely accepted as a measure of gender equality would be the increase in female educational enrolment, as we can see in the UK and France in the figure below.

Source: Ni Bhrolchain and Beaujouan 2012

Now, this establishes that there is an increase in the indicator we are claiming is a measure of gender equity, how does this fit into our logic of change model for demographic outcomes? The figure below presents age specific fertility rates which begin when the woman leaves full time education

Source: Ni Bhrolchain and Beaujouan 2012

Overall, we notice very little change between cohorts, once we take into account the termination of educational enrolment. This leads us to the conclusion that there is a strong association between the two to the extent that as much of 60% of fertility postponement is explained by our indicator of gender equality, namely female education. Therefore, once we actually operationalise gender equity beyond more than stereotypes, some reasonably strong relationships emerge

What is the hypothesised relationship?

The final problem with the claim is that gender equity will necessarily be associated with decreases in behaviours like fertility. This is not unreasonable at relatively early stages of the Second Demographic Transition: the difficulty in role combination between work and motherhood and educational enrolment (as we have seen already) would be expected to decrease the intensity of all demographic behaviours. However, the assumption that this relationship is monotonic has little basis in demographic theory. Indeed, once we get to a certain stage, gender equality is expected to increase fertility level: this has been proffered as an explanation for European fertility variation with more gender equal countries in Scandinavia benefiting from higher fertility rates, with more traditional countries in the South experiencing drag on fertility as conservative social norms clash with educational and labour market requirements for women. The underlying assumption that feminism will reduce fertility universally is assuming that a country is at an early stage of gender development and the second demographic transition: I am not sure that this hold for the dataset that Noah is using.